Acts of kindness need not be random. Even something as simple as a smile can brighten a day.

And kindness can be surprising when unexpected. Though a good surprise. Even though at times it may rob you of your speech. Or embarrass you for a moment until you realize that someone did something out of the goodness of their heart, lending a helping hand when it was needed most, though you never said a word, or had any expectations.

And as surely as I am typing this, I can say without any doubt that there are indeed earth bound angels. People who are just drawn to do good when they can. And in the giving, they give you a better gift than the gift itself. They give you hope, love and faith. Enough to keep a little for yourself, and plenty more to share with the rest of the world.

Monday Back to Work Blues

Sometimes it's funny. I'm sitting here waiting for the blogger post page to load so I can offer my last complaint about having to return to work this morning, and wham! I think of something funny to blog about when there is absolutely no time to write any of it down. Talk about dumb luck.

And considering my dumb luck has just run out, it's going to have to keep for another day. I must get myself together and to work and pretend I'm overjoyed to be back. A total lie. But at times one must manufacture such stories to themselves in order to get through a day.

Still, if I can conquer a Monday, I can do just about anything! Well, almost ...

And considering my dumb luck has just run out, it's going to have to keep for another day. I must get myself together and to work and pretend I'm overjoyed to be back. A total lie. But at times one must manufacture such stories to themselves in order to get through a day.

Still, if I can conquer a Monday, I can do just about anything! Well, almost ...

Vacations End

It's amazing how nine days of freedom can pass so quickly, almost in a blur, as my vacation is officially coming to its end. And it's a bit sad really, though my purse couldn't have afforded any more days of freedom, what with little trips here and there to amuse my daughter and myself and our need to shop for the upcoming school year.

But we did far more than just shopping. We toured local historical sites, visited a petting zoo where both my daughter and I had thoughts of pilfering a pygmy goat kid and making off with it into the sunset, and of course our unforgettable trip to the movies to see the March of the Penguins. A really interesting movie being that I've always been a penguin fan, but more so for the mating scene complete with romantic type orchestral music, and the sound of my nine year old giggling as she said, "That is just so wrong."

We went for picnics, took walks along the harbor, talked about silly things, talked about not so silly things and just enjoyed being able to spend time together without constraints of work or school. And to be honest, I'm more than a little sad to have to give all that up to return to life as normal. In a perfect world, vacations would be much more frequent then they are ...

But we did far more than just shopping. We toured local historical sites, visited a petting zoo where both my daughter and I had thoughts of pilfering a pygmy goat kid and making off with it into the sunset, and of course our unforgettable trip to the movies to see the March of the Penguins. A really interesting movie being that I've always been a penguin fan, but more so for the mating scene complete with romantic type orchestral music, and the sound of my nine year old giggling as she said, "That is just so wrong."

We went for picnics, took walks along the harbor, talked about silly things, talked about not so silly things and just enjoyed being able to spend time together without constraints of work or school. And to be honest, I'm more than a little sad to have to give all that up to return to life as normal. In a perfect world, vacations would be much more frequent then they are ...

Learning Our A, B and C's

The thing about silence is that sometimes you never know what really caused it. To some the act of going mute is more like a disappearing act, vanishing into time itself as it passes one day into the next. To others, silence becomes a response. Silence for silence. An even exchange. Eye for an eye logic. Because "A" never called to talk to "B","B" has decided not to talk to "A" ... That's how silence works.

Because when you're silent, it's not always that you have nothing to say. It's the exact opposite. The reality is having so much to say that you don't even know where to begin, and so you don't. Because you know two things ...

So "B" has decided to get out of the house for a little while today and meet up with "C" because it's nice to know, that there are exactly 25 other letters to choose from.

Because when you're silent, it's not always that you have nothing to say. It's the exact opposite. The reality is having so much to say that you don't even know where to begin, and so you don't. Because you know two things ...

(1) If you were important to "A" then "A" wouldn't have let almost an entire week pass without some sort of conversation ...

and

(2) Chasing anyone down to gain their attention isn't something that "B" is willing to do anymore.

So "B" has decided to get out of the house for a little while today and meet up with "C" because it's nice to know, that there are exactly 25 other letters to choose from.

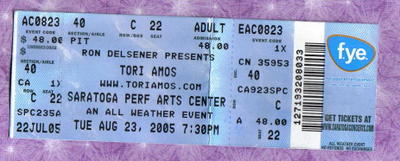

Something More Than Wonderful

I'm way too tired to write anything that would do last night's concert any justice, when really there is just SO much to tell ... I will however say that our seats were phenomenal. Dead center. Third row from the stage. Wonderful. And I swear, Tori looked right at me and smiled ... Most likely in response to the goofy look I must have had on my face. I mean WOW! She sang almost ALL of my most favorite songs and ended with my most favorite of all ... Hey Jupiter.

Anyhoo ... I'm in need of a nap, while poor Brenda, M&M and KM are all working themselves silly on very little sleep ... Sorry guys! If it helps, KC and I spent most of the day at the mall shopping ... Or at least thinking about shopping.

But last night was the absolute TOPS! Before, during and after the concert ...

08/23/05

Saratoga Springs, NY

Saratoga Performing Arts Center

Set List (While I love all of her music, there are some I love more than others.)

Original Sinsuality

Little Amsterdam

Icicle

Goodbye Pisces

China (I sing this one in the shower ALL of the time.)

Spark

Siren (Driving in the car, this is always a good one to have cranked to full volume.)

And Dream of Sheep (Cover song #1. Does anyone know who the original artist is or was?)

Moonshadow (Cover song #2.)

Mother

Sugar

Jamaica Inn

Strange (This is one of the songs I really wanted to hear at the last concert I attended.)

The Beekeeper

Bells For Her

Putting the Damage On

Apollo's Frock

Hey Jupiter (Dakota Version) (My ALL time most FAVORITE Tori song ... Ever.)

The Road to SPAC

Sometimes the most wonderful thing you can say to someone is thank you. You don't have to list your reasons, you don't have to explain all the who, what, where and why's. You simply have got to say it from the heart and mean it. And so I'm saying thanks from the comfort of my living room, by putting my writing on this wall, because there's a good chance in a crowd of a thousand voices strong, that my gratitude may not be heard.

But it's there. And it's here. And it reaches its own arms out to embrace the world in its own small way. One thought at a time, one word at a time.

That being said, I believe there's a concert that I need to get myself together for. But please, don't wait up for me ... I have a feeling I won't be home until tomorrow's light.

But it's there. And it's here. And it reaches its own arms out to embrace the world in its own small way. One thought at a time, one word at a time.

That being said, I believe there's a concert that I need to get myself together for. But please, don't wait up for me ... I have a feeling I won't be home until tomorrow's light.

Fictionally Speaking

Clever girls aren't known for their looks. Maybe they have a nice smile, or relatively good hair, but the moment they're gone from view, they aren't anything more than forgotten.

The truth of the matter is that beauty and the lack thereof speaks volumes and it gives us something to blame when things go wrong. Others might call this a case of insecurities. The blaming of happenstance for all the little things that go in a direction completely of their own. I'm more apt to call it an ugly girl's reality.

And the reality is that everything is out of reach.

Sure, you can try to be good. Always doing and saying the right things, at the right time, to the right people. But eventually good girl logic gives in and says, "Maybe this wasn't such a good idea after all. Maybe I should call it quits. I didn't really want what I said I really wanted anyway."

An ugly girl will lie to herself twenty times a day if need be. Building up her ladder rung by rung, only to decide at the very end of the day that her courage to climb has all but vanished. And who could blame the girl for being more cautious in her climbing when she herself is afraid of heights?

To most people this sort of logic wouldn't seem to make sense, unless they really understood that sometimes being on the not so pretty side of life, is more like being the little matchstick girl pressing her face against cold glass to watch the warmth and merriment within, all the while wishing that somehow, she too could come in from the cold.

wouldn't seem to make sense, unless they really understood that sometimes being on the not so pretty side of life, is more like being the little matchstick girl pressing her face against cold glass to watch the warmth and merriment within, all the while wishing that somehow, she too could come in from the cold.

The truth of the matter is that beauty and the lack thereof speaks volumes and it gives us something to blame when things go wrong. Others might call this a case of insecurities. The blaming of happenstance for all the little things that go in a direction completely of their own. I'm more apt to call it an ugly girl's reality.

And the reality is that everything is out of reach.

Sure, you can try to be good. Always doing and saying the right things, at the right time, to the right people. But eventually good girl logic gives in and says, "Maybe this wasn't such a good idea after all. Maybe I should call it quits. I didn't really want what I said I really wanted anyway."

An ugly girl will lie to herself twenty times a day if need be. Building up her ladder rung by rung, only to decide at the very end of the day that her courage to climb has all but vanished. And who could blame the girl for being more cautious in her climbing when she herself is afraid of heights?

To most people this sort of logic

wouldn't seem to make sense, unless they really understood that sometimes being on the not so pretty side of life, is more like being the little matchstick girl pressing her face against cold glass to watch the warmth and merriment within, all the while wishing that somehow, she too could come in from the cold.

wouldn't seem to make sense, unless they really understood that sometimes being on the not so pretty side of life, is more like being the little matchstick girl pressing her face against cold glass to watch the warmth and merriment within, all the while wishing that somehow, she too could come in from the cold.

Spit Spot

For once I'm thankful for overcast skies and the chill breeze that's blowing lightly through the trees. I slept in this morning, waking up at 10:18 precisely and thought for one moment to myself how comfortable my bed was, and then mentally ran down my somewhat lengthy list of things to do as my bare feet made contact with the rug.

But now I've come downstairs to survey the mess before me, school supplies that need to be put away, laundry that needs to be done, cats to be fed, and a daughter that needs to help with some of the smaller chores just as soon as I get our breakfast under way.

I hate waking up to the thought of chores, but the simple truth of the matter is they need to be done in order to enjoy the rest of the day, and for us, the rest of the week actually ... And so I really should set myself in motion.

Other than the Tori concert on Tuesday, KC and I are planning on making no plans but just sort of winging it every day this week so things should be interesting ... Sometimes it's far better to go with the flow than bog yourself down with the making of plans. Regardless, I think I'll load my camera up with film and see what images might come forth.

But now I've come downstairs to survey the mess before me, school supplies that need to be put away, laundry that needs to be done, cats to be fed, and a daughter that needs to help with some of the smaller chores just as soon as I get our breakfast under way.

I hate waking up to the thought of chores, but the simple truth of the matter is they need to be done in order to enjoy the rest of the day, and for us, the rest of the week actually ... And so I really should set myself in motion.

Other than the Tori concert on Tuesday, KC and I are planning on making no plans but just sort of winging it every day this week so things should be interesting ... Sometimes it's far better to go with the flow than bog yourself down with the making of plans. Regardless, I think I'll load my camera up with film and see what images might come forth.

At the Present Time ...

Preparing to go on vacation, even if you're not really going anywhere other than your own home and a few random day trips here and there, can be mighty stressing. Stressing because being out of the office for an entire week means that everything in your office has to be in tip top shape. Nothing can be out of order. Nothing can be left in a to do pile. Everything has got to be neat, organized and done. And really, it's the only way you'll be able to enjoy your vacation ... With no worries.

Worrisome however is my nephew who took a nasty spill off his skateboard two days ago and is still in the hospital awaiting a verdict on what actually may be wrong with him. If the latest rumor proves true, then the poor kid will be having surgery tomorrow on his leg ... Guess I need to make a few phone calls and find out the facts, though judging by his spirits today (I made a quick visit to the hospital during my lunch hour) he seems to be fine, other than the normal complaints of bad hospital food and sleep that is constantly disturbed.

In other news, the Tori Amos concert is less than a week away and I am giddy with excitement, or at least I would be if I weren't so damn tired. These damn dreams that insist on playing out every night in my head are really starting to get on my nerves, as I wake up more tired than I was when I went to bed. Argh.

Anyhoo, I just wanted to pen something quick to see if I could remember how to blog as I've been doing quite horrid lately. Must be these summer hours that are keeping me busy and on the go ...

Worrisome however is my nephew who took a nasty spill off his skateboard two days ago and is still in the hospital awaiting a verdict on what actually may be wrong with him. If the latest rumor proves true, then the poor kid will be having surgery tomorrow on his leg ... Guess I need to make a few phone calls and find out the facts, though judging by his spirits today (I made a quick visit to the hospital during my lunch hour) he seems to be fine, other than the normal complaints of bad hospital food and sleep that is constantly disturbed.

In other news, the Tori Amos concert is less than a week away and I am giddy with excitement, or at least I would be if I weren't so damn tired. These damn dreams that insist on playing out every night in my head are really starting to get on my nerves, as I wake up more tired than I was when I went to bed. Argh.

Anyhoo, I just wanted to pen something quick to see if I could remember how to blog as I've been doing quite horrid lately. Must be these summer hours that are keeping me busy and on the go ...

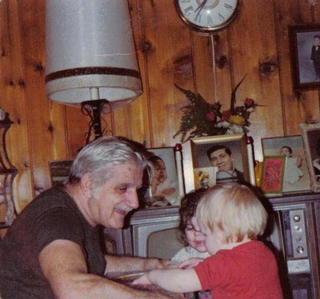

Following a Cloud of Thoughts

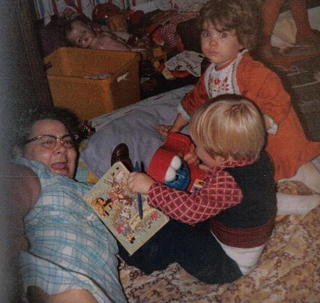

When she was young, the world was only as big as the sky above her. And on top of the old red dog house, she'd count the stars at night and think to herself that clouds were made up of all the souls that went to heaven. And it made her feel better to think of her grandfather as a cloud, floating high above with a watchful and loving eye.

She always hoped she'd make him proud, the grandfather that existed in her mind who became perfection, because he wasn't there to prove her wrong. His death in the youngest years of her life had immortalized him, not as an ordinary man but as a combination of all things wonderful. And so she strove to please his memory.

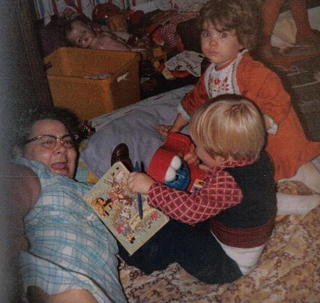

She learned at her grandmother's knee the old ways of doing things, spending most every weekend at her Nani's when she should have been next door at her father's. And Nani spoiled her rotten, not with gifts but with stories told over bowls of soup heaping with tubettini topped with Romano cheese. And at night they would watch TV together, sometimes staying up late enough to watch Johnny Carson before going to bed where she would cuddle up close to her grandmother's side, comforted by the sound of her snores and the wall behind her.

And in the morning, they would watch the Catholic mass on TV, since it was too hard for Grandma to go in person. And after mass, they'd watch WWF Wrestling because Grandma had a soft spot for Hulk Hogan and couldn't stand the little man with the microphone that always seemed to be jumping around with "ants in his pants" as Grandma would say.

I remember well the glint in her eye when she would watch, and the sly smile that would sometimes set on her face when no one was looking. And I remember thinking how lucky I was, because I was the only person who really knew that Grandma wasn't as old as everyone else thought she was. No. I remember thinking that she was just like me, full of mischief that no one ever really knew about.

She always hoped she'd make him proud, the grandfather that existed in her mind who became perfection, because he wasn't there to prove her wrong. His death in the youngest years of her life had immortalized him, not as an ordinary man but as a combination of all things wonderful. And so she strove to please his memory.

She learned at her grandmother's knee the old ways of doing things, spending most every weekend at her Nani's when she should have been next door at her father's. And Nani spoiled her rotten, not with gifts but with stories told over bowls of soup heaping with tubettini topped with Romano cheese. And at night they would watch TV together, sometimes staying up late enough to watch Johnny Carson before going to bed where she would cuddle up close to her grandmother's side, comforted by the sound of her snores and the wall behind her.

And in the morning, they would watch the Catholic mass on TV, since it was too hard for Grandma to go in person. And after mass, they'd watch WWF Wrestling because Grandma had a soft spot for Hulk Hogan and couldn't stand the little man with the microphone that always seemed to be jumping around with "ants in his pants" as Grandma would say.

I remember well the glint in her eye when she would watch, and the sly smile that would sometimes set on her face when no one was looking. And I remember thinking how lucky I was, because I was the only person who really knew that Grandma wasn't as old as everyone else thought she was. No. I remember thinking that she was just like me, full of mischief that no one ever really knew about.

A Sudden Wildness

I have been calm. As calm as an ocean wave on a silent sea rocking to and fro with the gentleness of a baby held in her mother's arms. I have been still, cautiously moving with eyes that track my progress in every direction, taking small steps, not daring to live too loud. I have sought silence and been content to follow my routine, one slow day into the next. And it has been enough, this quiet existence.

But now an odd restlessness sits outside my door waiting to be answered. And it will not be silenced in its attempt to draw me back and blur the lines I thought never to cross again. Instead the 19 year old version of myself smiles wickedly and speaks to me in tones hard to ignore, a sinner to her own seducing with memories of a wildness that are boiling just beneath my skin.

But now an odd restlessness sits outside my door waiting to be answered. And it will not be silenced in its attempt to draw me back and blur the lines I thought never to cross again. Instead the 19 year old version of myself smiles wickedly and speaks to me in tones hard to ignore, a sinner to her own seducing with memories of a wildness that are boiling just beneath my skin.

A Season of Hay

Haying season in August always brings back memories of the farm and a family that I grew up loving as if they were my own ... And not just because I was in love with their eldest son from the time I put on my first training bra until I graduated my way into a C Cup. They were the kind of people who drew you in until you felt very much like one of their own. The kind of people who lent a helping hand when it was needed and let you call their house a home away from home.

I grew up a country girl, playing hide and seek in hay mounts, swinging from ropes that hung down from the ceiling and learned quickly where to step, when to step and where not to step and what to listen and look for as I was stepping. Raised tails were not to be taken lightly.

I played with barn yard kittens, fell in love with every calf, and helped with whatever I could, whenever I could, just for the simple joy of spending as much time there as possible. I loved taking rides in the tractor, chasing errant cows down when they refused to come in from pasture, and climbing into the hay wagon as we bumped and jolted our way down a rutty country road in search of a hay strewn field.

The eldest son - who at my tender age of twelve was the love of my life, though he was five years my junior - would already be out in the field waiting for his younger brother and I to bring the empty wagon to trade out with the full. And though he wasn't the most patient of boys, what with the way he would boss around his little brother and roll his eyes at my doe eyed antics, I was sure that he loved me too ... Why else would he have offered me a piece of Wrigley's Spearmint gum if not to say he cared?

After the sharing of such a meaningful piece of gum, Little Case (whom on last inspection was well over six feet tall) and I would ride back to the farm, him driving happily away with a sweet smile on his face and me usually playing co-pilot from my perch on the fender, staring wistfully after his brother. Ah parting, it was such sweet sorrow ...

But back at the farm, we were all business, young Casey backing the wagon up just a few feet away from the conveyor belt. And when the belt started groaning, the chains sounded like a stick on a snare drum beating increasingly faster as gravity was put to the test. Grabbing a bale at a time, Casey and I worked out a silent pattern of taking opposite turns of tossing. Sometimes he'd be high on the load tossing the bales down while I pitched them onto the belt, and when my arms ached from the exertion, I'd switch out and push the bales down to land at his feet for him to toss.

For those of you who have never lived on a farm, or grew up near one, there is a quick lesson you learn about throwing bales ... One being that bales that don't land quite right on the conveyor belt have an extremely bad habit of coming back down when you least expect them to, and mostly on top of your own head if you're not paying attention. So every throw was like taking a money shot, get it wrong and the price to pay could be anywhere from losing three bales over the side, taking a full body shot of bale or getting one wedged up high in the door that opened up into the mount, at which point the whole process would have to stop to shut everything down and someone - though usually never me - would have to scale the conveyor to unplug the impediment.

And haying was always a hot process. Smart girls and boys knew better than to wear shorts, and short sleeved tops when doing their time in the wagons. And for those doubting Thomases who thought they knew better and came dressed for a day at the beach, they soon found out that hay was neither soft nor kind to tender skin left exposed. Instead they found out the meaning of hay rash, and heat rash, and previously smooth skin left pink and irritated with little dots all over.

But I loved it. Loved every little minute of it. Loved the thrill of being outside, being with my friends, and the two dollars I got a wagon for helping. To me, it was a slice of heaven.

Sadly, as the way things often go for small family based farms in America, there just wasn't enough time, money and people to keep the operation out of the red. The family farm that I grew up loving has long been left abandoned, it's out buildings falling down and the house unnaturally empty with its front door swinging wide open whenever an errant breeze happens to chance its way, while a single rope hanging from the haymount still, beckons the memory to recall what once was inside ...

There is no road to happiness ... Just the road.

When a woman speaks her mind it's because she's asking you to listen. To hear what she has to say, because she thinks it's important enough to be said.

And women have so much to say that sometimes they say nothing at all. They pack up words and pile them on their shoulders, carrying them around all day like an extra load of burden that only they can carry, just to prove that they can.

Far away friends have told me the importance of letting it all go ... To live life more as a comedy than tragedy. To give only what I can give, without losing the essentialness of myself and those things that make me happy.

I just wanted to let them know that I'm listening ...

And women have so much to say that sometimes they say nothing at all. They pack up words and pile them on their shoulders, carrying them around all day like an extra load of burden that only they can carry, just to prove that they can.

Far away friends have told me the importance of letting it all go ... To live life more as a comedy than tragedy. To give only what I can give, without losing the essentialness of myself and those things that make me happy.

I just wanted to let them know that I'm listening ...

Don't Let It Bug You ...

When you have a bad day, there's one important thing you should always remember ... You could have been born a bug.

And as we all know, bugs don't exactly have the longest life spans. Some meet their ends - quite literally - on the front of our windshields, or are splattered like broken yolks with one swat of a fly swatter. Others meet their ends by falling victim to a great white light, or finding themselves stuck in a hanging strip of glue. While some actually go the natural way and are gobbled up by spiders or even hungrier birds ... No matter how they go, the truth is this, when it comes to being low man on the food chain, bugs have got it bad ...

So when life seems hectic, crazy and full of stress, and all you want to do is pull every last strand of hair out of your head and cry, just remember this one thing ...

You could have been born a bug ...

And as we all know, bugs don't exactly have the longest life spans. Some meet their ends - quite literally - on the front of our windshields, or are splattered like broken yolks with one swat of a fly swatter. Others meet their ends by falling victim to a great white light, or finding themselves stuck in a hanging strip of glue. While some actually go the natural way and are gobbled up by spiders or even hungrier birds ... No matter how they go, the truth is this, when it comes to being low man on the food chain, bugs have got it bad ...

So when life seems hectic, crazy and full of stress, and all you want to do is pull every last strand of hair out of your head and cry, just remember this one thing ...

You could have been born a bug ...